Course Outline

-

segmentGetting Started (Don't Skip This Part)

-

segmentStatistics and Data Science: A Modeling Approach

-

segmentPART I: EXPLORING VARIATION

-

segmentChapter 1 - Welcome to Statistics: A Modeling Approach

-

segmentChapter 2 - Understanding Data

-

segmentChapter 3 - Examining Distributions

-

segmentChapter 4 - Explaining Variation

-

segmentPART II: MODELING VARIATION

-

segmentChapter 5 - A Simple Model

-

segmentChapter 6 - Quantifying Error

-

segmentChapter 7 - Adding an Explanatory Variable to the Model

-

segmentChapter 8 - Models with a Quantitative Explanatory Variable

-

segmentPART III: EVALUATING MODELS

-

segmentChapter 9 - Distributions of Estimates

-

segmentChapter 10 - Confidence Intervals and Their Uses

-

segmentChapter 11 - Model Comparison with the F Ratio

-

11.4 Comparing Models Using the F Ratio

-

segmentChapter 12 - What You Have Learned

-

segmentFinishing Up (Don't Skip This Part!)

-

segmentResources

list full book

11.4 Comparing Models Using the F Ratio

We have now established that both PRE and F, like any sample statistic or parameter estimate, have sampling distributions. We used randomization to generate sampling distributions for both PRE and F, and calculated the proportion of simulated samples that would have PREs or Fs as extreme as the ones observed in the Tipping study (PRE = .0729 and F = 3.305). We also explored another way of thinking about the sampling distribution of F: to use the mathematical F distribution.

It is important to note that both PRE and F are comparisons of two quantities in the form of a ratio. In the case of PRE, we are comparing the SS accounted for by our model to the total SS in the outcome variable. With F, we are comparing two different estimates of variance: one based on our model, the other based on variation leftover after our model is fit.

Both PRE and F represent a comparison of two models: the one that includes an explanatory variable with the one that does not (the empty model). Even though the analysis is represented in a single ANOVA table, we really are comparing these two competing models of the Data Generating Process.

In the empty model of the DGP, we assume that variation in the outcome \(Y\) is purely random (or at least so random that we cannot explain it). So the best we can do is just the mean of the population.

\[Y_i = \beta_0 + \epsilon_i\]

In the two-group model of the DGP, we assume that not all of the variation is random, and that some of it can be explained by the explanatory variable.

\[Y_i = \beta_0 + \beta_1X_i + \epsilon_i\]

We’ll estimate those parameters of the DGP with the best-fitting estimates from our sample. That’s when we switch to using the \(Y_i = b_0 + e_i\) and \(Y_i = b_0 + b_1X_i + e_i\) notation. But now we know that even our best-fitting estimates have a fundamental problem: they would have been different if we had collected a different sample. Even the PRE and F ratio used to compare the best-fitting simple model versus best-fitting complex model have sampling variation.

Hypothesis Testing and Model Comparison

If you have studied statistics before, you no doubt have heard the term “null hypothesis.” When we refer to the empty model it is fundamentally the same as the null hypothesis: it’s the model that we would obtain if there were no effect of the explanatory variable on the outcome. In fact, we sometimes call it the null model.

When we randomize a sampling distribution of F, we are examining the distribution of possible Fs that could have occurred if the null model was true, so any differences we observe are only due to random chance. If the null model is true, the actual value of \(\beta_1\) would be 0. The null sampling distribution basically lays out all the possible Fs we could have generated from a DGP of random chance.

Once that stage is set, we could then look at the F statistic we calculated from our own sample, and evaluate whether or not we think it could have happened by chance alone. If we think our F was unlikely to have occurred if the null model were true, then we reject the null model in favor of our more complex model. But if we think it’s possible that our observed F was just a fluke, and that the null model could, in fact, be true, then we keep the null model.

Just as the tails of the t distribution never actually reach 0, so does the right-side tail of the F distribution never reach a probability of 0. What this means is that no matter how large our F statistic is for a particular sample, there is always a possibility, even if small, that our sample result happened by chance and that the null model is, in fact, true. For practical purposes, then, we need to set a criterion for what counts as “unlikely” (it’s called an alpha level), a probability of being wrong that we are willing to accept. Traditionally, that alpha level is set at .05.

As a general rule of thumb, if F is greater than 4, there is less than a .05 probability that the true effect of the explanatory variable (or, in GLM terms, the true value of the parameter \(\beta_1)\) is equal to 0. We can get an exact probability using the xpf() function, but for general purposes, the rule of 4 won’t be that far off, though it will vary depending on degrees of freedom. If the probability is less than .05, we generally will say that the result is statistically significant, meaning that we are confident that the true value of \(\beta_1\) is not equal to 0.

If we observe an F with a probability greater than .05, we typically retain the empty model. In the language of null hypothesis testing, we say that we have “failed to reject the null hypothesis.” It’s important to note that when we decide to retain the empty model it doesn’t mean that the empty model is true. For it to be true, the value of \(\beta_1\) would have to be exactly equal to 0. But we don’t know that it is equal to 0. All we know is that, within our acceptable margin of error, we are not confident that it is not equal to 0. Could it be .1? -.003? Of course it could be any of these. And it also could be 0.

Hypothesis Testing with the Tipping Experiment

Let’s put all these ideas together in the context of the Tipping Experiment. Use the following code window to fit the null model (where any differences between the Smiley Face and Control group are just caused by chance) and the complex model.

require(tidyverse)

require(mosaic)

require(Lock5Data)

require(okcupiddata)

require(supernova)

# fit the null model (also print out best-fitting estimates)

# fit the complex model (also print out best-fitting estimates)

# fit the null model (also print out best-fitting estimates)

lm(Tip ~ NULL, data = TipExperiment)

# fit the complex model (also print out best-fitting estimates)

lm(Tip ~ Condition, data = TipExperiment)

ex() %>% {

check_function(., "lm", index = 1) %>%

check_result() %>% check_equal()

check_function(., "lm", index = 2) %>%

check_result() %>% check_equal()

}

Call:

lm(formula = Tip ~ NULL, data = TipExperiment)

Coefficients:

(Intercept)

30.02

Call:

lm(formula = Tip ~ Condition, data = TipExperiment)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) ConditionSmiley Face

27.000 6.045Here are the best-fitting estimates put into our GLM notation.

Null model: \(Y_i = 30.02 + e_i\)

Complex model: \(Y_i = 27 + 6.05X_i + e_i\)

Now let’s look at some statistics that compare these two models (PRE and F ratio) by printing out the supernova table using the code window below.

require(tidyverse)

require(mosaic)

require(Lock5Data)

require(okcupiddata)

require(supernova)

Empty.model <- lm(Tip ~ NULL, data = TipExperiment)

Condition.model <- lm(Tip ~ Condition, data = TipExperiment)

# print out the supernova table comparing these two models

Empty.model <- lm(Tip ~ NULL, data = TipExperiment)

Condition.model <- lm(Tip ~ Condition, data = TipExperiment)

# print out the supernova table comparing these two models

supernova(Condition.model)

ex() %>% check_output_expr("supernova(Condition.model)")

Analysis of Variance Table

Outcome variable: Tip

Model: lm(formula = Tip ~ Condition, data = TipExperiment)

SS df MS F PRE p

----- ----------------- ------- -- ------ ----- ------ -----

Model (error reduced) | 402.02 1 402.02 3.305 0.0729 .0762

Error (from model) | 5108.95 42 121.64

----- ----------------- ------- -- ------ ----- ------ -----

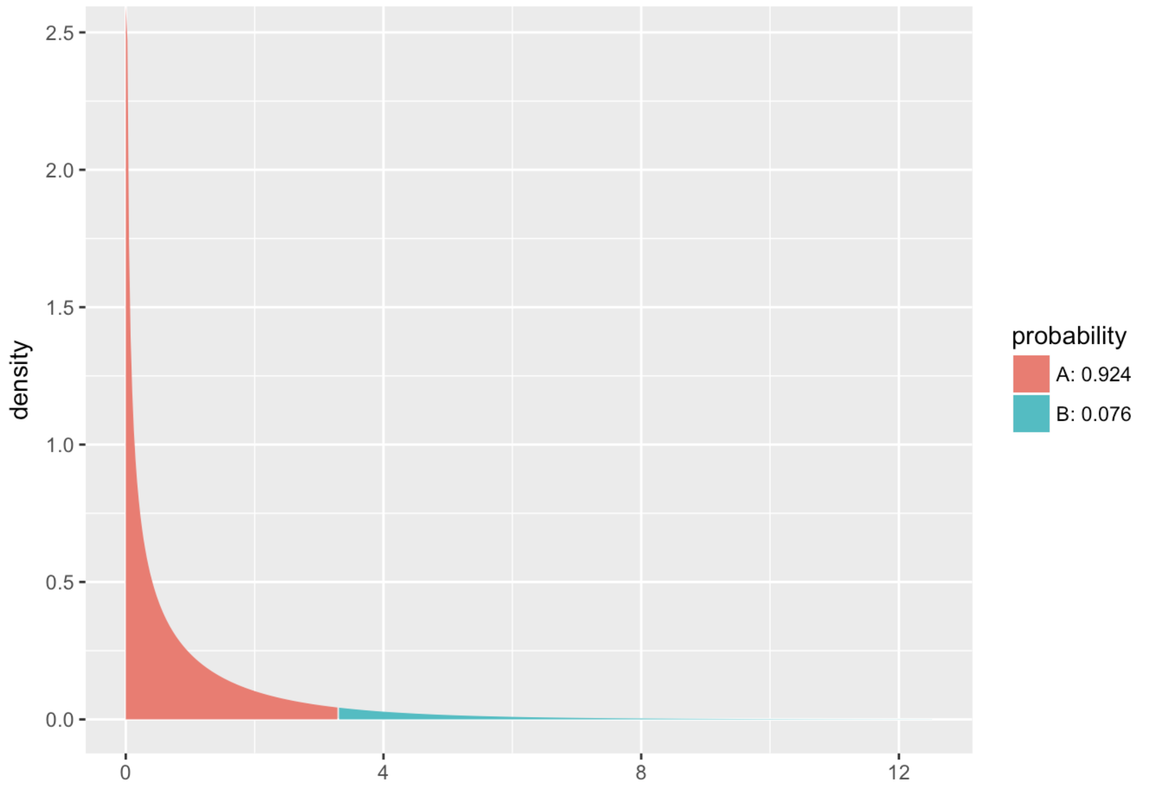

Total (empty model) | 5510.98 43 128.16In the background, R has examined the F distribution made of Fs that could have been generated by the empty model (if you want to take a look at it, you just need to use the xpf() function as we did before). Then R took a look at where our sample F appeared relative to all those possible Fs and printed out the p-value in our supernova table.

sampleF <- fVal(Tip ~ Condition, data = TipExperiment)

xpf(sampleF, df1 = 1, df2 = 42)

If our sample F was in the “unlikely” area—the .05 most extreme Fs that could have been generated by the empty model—we would conclude that our sample F was unlikely to have been generated by this process. But our sample is not one of the .05 most extreme Fs! It’s one of the .076 highest Fs generated by randomness! And the sample F corroborates this story because 3.305 is not greater than 4.

What now? Is our empty model likely or unlikely to have generated our sample F? Although .08 may not seem very likely to a casual observer, it is more likely than a .05 likelihood. According to our pre-set standards of what counts as “unlikely,” our empty model is not unlikely. This means \(\beta_1\), the increment, might be 0. We shouldn’t get rid of the empty model in favor of the complex model.

What’s a t test?

You may have heard of a t test, or even studied it in a previous statistics class. The t test is used to test the statistical significance between the means of two independent groups. We analyze that same situation by fitting the two-group model, and then using F to assess the difference between the two groups.

It turns out that in the case of comparing two groups, t and F are exactly the same, and the resulting p value will be the same. If you want the t statistic, you can just run your supernova(), find F, and then take the square root of F. That’s the t statistic (also called sample t). Just as an F statistic is considered significant if it’s more extreme than 4, a t statistic is considered significant if it’s more extreme than \(\pm2\).

We use F instead of t because it will work in virtually any situation in which you want to evaluate statistical models, whereas the t test is more limited. But if someone asks you, now you know what a t test is.

Interpreting the Model Comparison

In the case of the Tipping Experiment, the model comparison could yield a fairly straightforward interpretation. If we do the experiment and find an F that is greater than 4 (which we didn’t), we could conclude that the drawing of a smiley face on a check causes restaurant patrons to tip more.

This causal interpretation is not purely the result of statistical analysis. It is, instead, the combination of statistical analysis and study design. In this case, we have the advantage of random assignment: each table at the restaurant was randomly assigned to either get a smiley face or not. For this reason, if we detect a difference between the groups we can assume it is due to this experimental manipulation and not something else.

But if there had been a correlational design, and tables were not randomly assigned to conditions, we might do the same statistical analysis and get the same F. But we would need to consider other interpretations. If everyone who got the smiley face had had one server, and everyone without the smiley face, another, we would have to consider that it might be the server, and not the smiley face, that was causing the difference.

In the absence of random assignment, we can rule out that the F we observed was simply due to sampling variation, and we can adopt the more complex model. But we still need to always wonder if our interpretation of the complex model is correct, or if there may be some confounding variable we haven’t considered. Design and analysis are both important, and must be considered together.