Course Outline

-

segmentGetting Started (Don't Skip This Part)

-

segmentStatistics and Data Science: A Modeling Approach

-

segmentPART I: EXPLORING VARIATION

-

segmentChapter 1 - Welcome to Statistics: A Modeling Approach

-

segmentChapter 2 - Understanding Data

-

segmentChapter 3 - Examining Distributions

-

segmentChapter 4 - Explaining Variation

-

segmentPART II: MODELING VARIATION

-

segmentChapter 5 - A Simple Model

-

segmentChapter 6 - Quantifying Error

-

segmentChapter 7 - Adding an Explanatory Variable to the Model

-

segmentChapter 8 - Models with a Quantitative Explanatory Variable

-

segmentPART III: EVALUATING MODELS

-

segmentChapter 9 - Distributions of Estimates

-

segmentChapter 10 - Confidence Intervals and Their Uses

-

segmentChapter 11 - Model Comparison with the F Ratio

-

11.6 Using the F Ratio to Compare Multiple Groups

-

segmentChapter 12 - What You Have Learned

-

segmentFinishing Up (Don't Skip This Part!)

-

segmentResources

list full book

11.6 Using the F Ratio to Compare Multiple Groups

Back in Chapter 3 we developed a model we called the Height3Group.model to explain thumb length (Thumb). We created a categorical explanatory variable by divvying up the students into three groups by their Height using the ntile() function. We then plotted Thumb as a function of Height3Group, pictured above.

We developed the idea at that time that Height3Group explains some of the variation of thumb length in our sample. We noted that just by visually inspecting the boxplots, you can see that knowing someone’s height (whether they are short, medium, or tall) will help you make a slightly better guess as to the length of their thumb than if you didn’t know which height category they were in.

From the boxplots, we can see a pretty clear relationship between height and thumb length in our sample. But this relationship could be the result of random sampling variation. Just because we have a relationship in our sample, it doesn’t mean the same relationship exists in the DGP.

We know a lot more now than we did in Chapter 3! Let’s see how we could re-cast this question in terms of model comparison using F. The two models we want to compare are the three-group model and the empty model in the population. Here they are in GLM notation:

\(Y_i=\beta_{0}+\beta_{1}X_{1i}+\beta_{2}X_{2i}+\epsilon_i\)

\(Y_i=\beta_{0}+\epsilon_i\)

Fit these models (the Height3Group model and the empty model) in the code window below.

require(tidyverse)

require(mosaic)

require(Lock5Data)

require(okcupiddata)

require(supernova)

Fingers$Height3Group <- factor(

ntile(Fingers$Height, 3),

levels = 1:3,

labels = c("short", "medium", "tall")

)

# fit and print the Height3Group model of Thumb length

# fit and print the empty model of Thumb length

# fit and print the Height3Group model of Thumb length

lm(Thumb ~ Height3Group, data = Fingers)

# fit and print the empty model of Thumb length

lm(Thumb ~ NULL, data = Fingers)

ex() %>% {

check_function(., "lm", index = 1) %>%

check_result() %>% check_equal()

check_function(., "lm", index = 2) %>%

check_result() %>% check_equal()

}

Call:

lm(formula = Thumb ~ Height3Group, data = Fingers)

Coefficients:

(Intercept) Height3Groupmedium Height3Grouptall

56.071 4.153 8.023

Call:

lm(formula = Thumb ~ NULL, data = Fingers)

Coefficients:

(Intercept)

60.1In the next code window, run thesupernova() function on the Height3Group model to look at how it compares with the empty model.

require(tidyverse)

require(mosaic)

require(Lock5Data)

require(okcupiddata)

require(supernova)

Fingers$Height3Group <- factor(

ntile(Fingers$Height, 3),

levels = 1:3,

labels = c("short", "medium", "tall")

)

Height3Group.model<-lm(Thumb ~ Height3Group,data = Fingers)

# print the ANOVA table comparing Height3Group.model to the empty model

Height3Group.model<-lm(Thumb ~ Height3Group,data = Fingers)

# print the ANOVA table comparing Height3Group.model to the empty model

supernova(Height3Group.model)

ex() %>% check_output_expr("supernova(Height3Group.model)")

Analysis of Variance Table

Outcome variable: Thumb

Model: lm(formula = Thumb ~ Height3Group, data = Fingers)

SS df MS F PRE p

----- ----------------- ------- --- ------- ------ ------ -----

Model (error reduced) | 1690.4 2 845.220 12.774 0.1423 .0000

Error (from model) | 10189.8 154 66.167

----- ----------------- ------- --- ------- ------ ------ -----

Total (empty model) | 11880.2 156 76.155Based on the F statistic, we can say that the complex model based on the group means of short, medium, and tall height does a significantly better job explaining thumb length than the simple model. It is highly unlikely that the F statistic we observed would have occurred just by chance. The effect is real.

On the other hand, although it makes sense for taller people to have longer thumbs, we wouldn’t want to say that being taller causes one to have longer thumbs. It seems likely that both are caused by other factors that, when working together, produce bigger people.

Randomizing to Compare Models

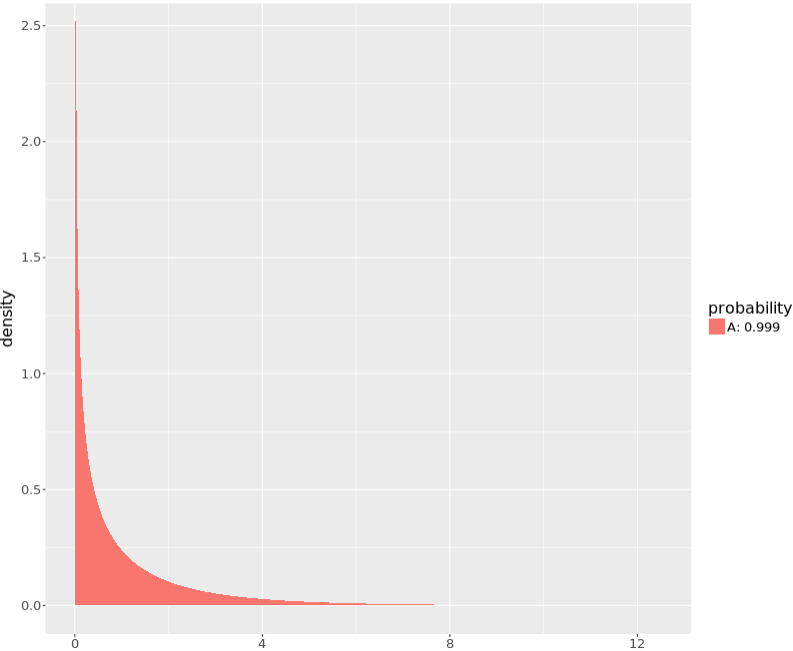

The p-level reported in the ANOVA table above (.0000) is the probability of getting an F as extreme or more extreme as 12.77. This probability was calculated using the F distribution for 2 and 154 degrees of freedom. We used the code below to generate this picture of the F distribution, putting in our sample F, and 2 and 154 as the respective degrees of freedoms.

sampleF <- fVal(Thumb ~ Height3Group, data = Fingers)

xpf(sampleF, df1 = 2, df2 = 154)[1] 0.9999926

The plot of the F distribution does not go out far enough to show you how extreme our sample F is. Notice that the x-axis only goes up to about 7, and our sample F was 12.77. The xpf() function also prints out the value of the coral red area in the console (.9999926). So the greenish-blue p-value would be .0000074 (or 1 - .9999926), too small to be depicted here or in the supernova table (which is limited to four decimal places).

What if you wanted to use randomization to get the sampling distribution of F instead of using the mathematical probability distribution for F? Remember, we’ll have to use our “If..” thinking and imagine a DGP where there is no real relationship between Thumb and Height3Group (any differences are just caused by chance).

Use the do(), fVal(), and shuffle() functions in the code window below to create a distribution of 1,000 F statistics from randomized samples. Save the randomized sampling distribution in a data frame called SDoF and print its first six rows.

require(tidyverse)

require(mosaic)

require(Lock5Data)

require(okcupiddata)

require(supernova)

Fingers$Height3Group <- factor(

ntile(Fingers$Height, 3),

levels = 1:3,

labels = c("short", "medium", "tall")

)

RBackend::custom_seed(101)

# create a sampling distribution of F generated from the empty model

# print the first 6 rows

# create a sampling distribution of F generated from the empty model

SDoF <- do(1000) * fVal(Thumb ~ shuffle(Height3Group), data = Fingers)

# print the first 6 rows

head(SDoF)

ex() %>% {

check_object(., "SDoF") %>% check_equal()

check_function(., "head") %>% check_result() %>% check_equal()

}

fVal

1 1.3160392

2 2.4330559

3 0.5621403

4 2.3157107

5 0.1789922

6 1.0597687Next, make a histogram of your randomized sampling distribution.

require(tidyverse)

require(mosaic)

require(Lock5Data)

require(okcupiddata)

require(supernova)

Fingers$Height3Group <- factor(

ntile(Fingers$Height, 3),

levels = 1:3,

labels = c("short", "medium", "tall")

)

RBackend::custom_seed(101)

# SDoF has been created for you

SDoF <- do(1000) * fVal(Thumb ~ shuffle(Height3Group), data = Fingers)

# plot these randomized F values in a histogram

# SDoF has been created for you

SDoF <- do(1000) * fVal(Thumb ~ shuffle(Height3Group), data = Fingers)

# plot these randomized F values in a histogram

gf_histogram(~fVal, data = SDoF, fill = "firebrick", alpha = .9)

ex() %>% check_function("gf_histogram") %>% {

check_arg(., "object") %>% check_equal()

check_arg(., "data") %>% check_equal()

}

Finally, use the code window below to tally the number of Fs out of the 1,000 randomized samples that were more extreme than the one observed in our study (sampleF).

require(tidyverse)

require(mosaic)

require(Lock5Data)

require(okcupiddata)

require(supernova)

Fingers$Height3Group <- factor(

ntile(Fingers$Height, 3),

levels = 1:3,

labels = c("short", "medium", "tall")

)

RBackend::custom_seed(101)

SDoF <- do(1000) * fVal(Thumb ~ shuffle(Height3Group), data = Fingers)

sampleF <- fVal(Thumb ~ Height3Group, data = Fingers)

# how many of the randomized Fs are greater than the sampleF?

SDoF <- do(1000) * fVal(Thumb ~ shuffle(Height3Group), data = Fingers)

sampleF <- fVal(Thumb ~ Height3Group, data = Fingers)

# how many of the randomized Fs are greater than the sampleF?

tally(~fVal > sampleF, data = SDoF)

ex() %>% {

check_object(., "sampleF") %>% check_equal()

check_function(., "tally") %>% check_result() %>% check_equal()

}

fVal > sampleF

TRUE FALSE

0 1000Clearly, the F we observed in our sample would have been very unlikely to have occurred if height (short, medium, or tall) was completely unrelated to thumb length. In terms of model comparison, this means that we should reject the simple (empty) model and adopt the complex model. The effect we observed could not be simply attributed to random sampling error. It’s a real relationship.

Interpretation of the Multi-Group F Test

When we compare the two-group model to the empty model, as we did in the comparisons of thumb length across sexes (male versus female), an extreme (as in large) F has a low likelihood of being generated by the empty model. That likelihood is called the p-value. When the p-value of the sample F is very low (smaller than .05), the difference between the two groups is significant at the .05 level. In other words, the difference between the two means is not just due to random sampling error, but to a real difference in means in the population. It allows us to say with 95% confidence that \(\beta_1\neq0\).

The interpretation of the three-group model compared to the empty model is a little different. In the three group model, if we observe an F with a less than .05 probability of occurring by chance, it means that if the means of the three groups are all equal to each other in the population (and notice the importance of the word “if” here), the F we observed would occur in fewer than .05 of random samples from the population.

If the probability is greater than .05, we are going to stick with the empty model, and just assume that there is no real difference between the means of the three groups. But if p < .05, it means that we can be confident that the three group means are not equal to each other. It does not tell us, however, which of the three group means are likely to differ, and which might not differ. It only tells us that the three have a less than .05 chance of being exactly the same as each other.

Simple Effects Tests

It might be good enough just to know that the complex model, the one that includes Height3Group, is significantly better than the empty model. But sometimes we want to know more than that. We want to know which of the three groups, specifically, differ from each other statistically, and which do not.

To figure this out we need to do three model comparisons, each designed to test the difference between pairs of the three groups. In the case of Height3Group, we would need to compare: 1) a model in which short versus medium people have different thumb lengths to one where they are the same (the empty model); 2) another in which medium versus tall people have different thumb lengths; and 3) a model in which tall versus short people have different thumb lengths.

The models being compared in all three cases would be represented the same way:

\(Y_{i}=b_{0}+e_{i}\)

\(Y_{i}=b_{0}+b_{1}X_{i}+e_{i}\)

In other words, we would be doing three separate two-group comparisons. Each comparison would yield a separate F statistic, which we could compare to the appropriate F distribution.